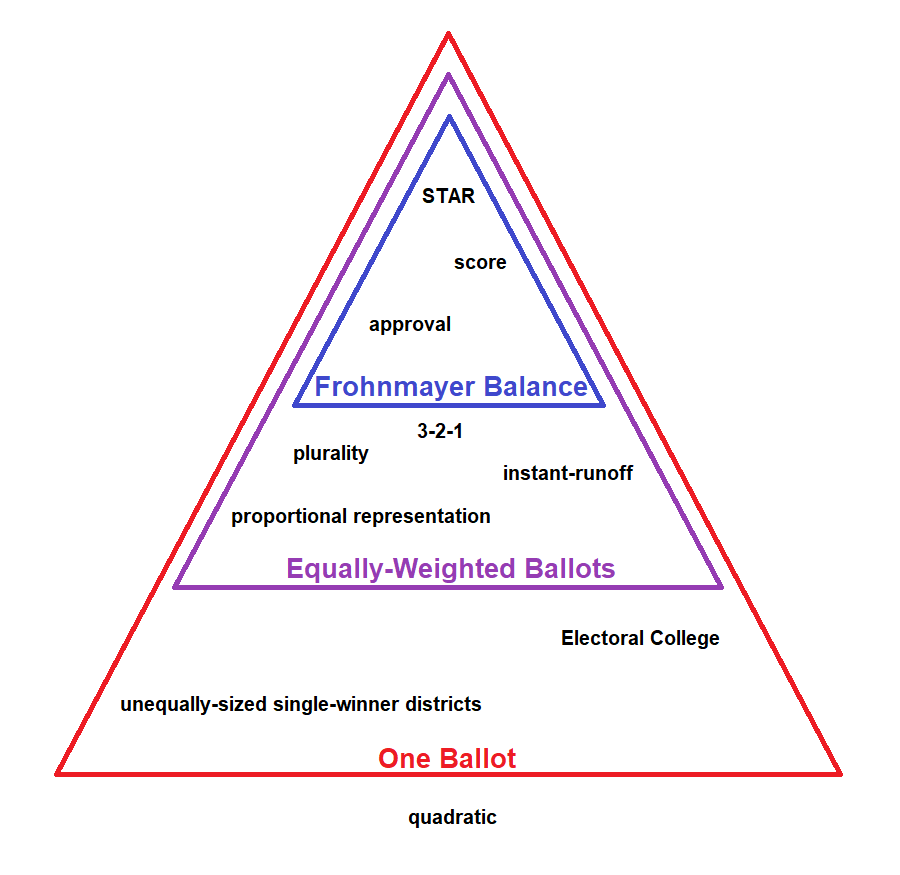

In a previous post, I laid out a hierarchy of three different possible meanings of one person, one vote (OPOV). The 1st level of OPOV required that each voter have exactly one ballot. The 2nd level required that each ballot have the same weight. Finally, the 3rd level required each possible ballot to be perfectly cancelled out by another possible ballot. I also created a combination Euler/pyramid diagram to demonstrate the relationship visually:

Before moving on, I’d like to formalize these types of OPOV a little more. I do think the 3rd level was defined well enough, but you can visit this page for the cancellation criterion if you need a refresher. For the 2nd level, it might not always be clear when the “weights” of two ballots are equal. It turns out that this has already been formalized through the anonymity criterion, which requires that for every fixed set of votes, the winner of the election remains the same regardless of which voters cast which of the votes from that set. This captures straightforward failure cases like the Electoral College, but also some stranger edge cases that might not have clear “weights” to compare.

When considering the 1st level, we run into the issue of defining what counts as “one ballot”. For a rated method with a 0-5 scale, we could give a voter an unfair advantage by giving them two 0-5 ballots and adding them together. We could also give them an advantage by giving them a single 0-10 ballot. But mathematically, these two advantages are one and the same, even though supposedly one has two ballots and the other only one.

We can solve this by requiring ballots to provide the same set of options for casting a vote to each voter. Now the single 0-10 ballot still violates this, even if it wouldn’t under a more literal interpretation of “one ballot”. I decided to formalize this idea into the identical input options (IIO) criterion. As a quick reality check, the IIO criterion is implied by the anonymity criterion, which means that any voting system1 passing anonymity must also pass IIO. This matches up with the idea that any voting system with equally-weighted ballots should also have exactly one ballot per voter, as shown in the above diagram.

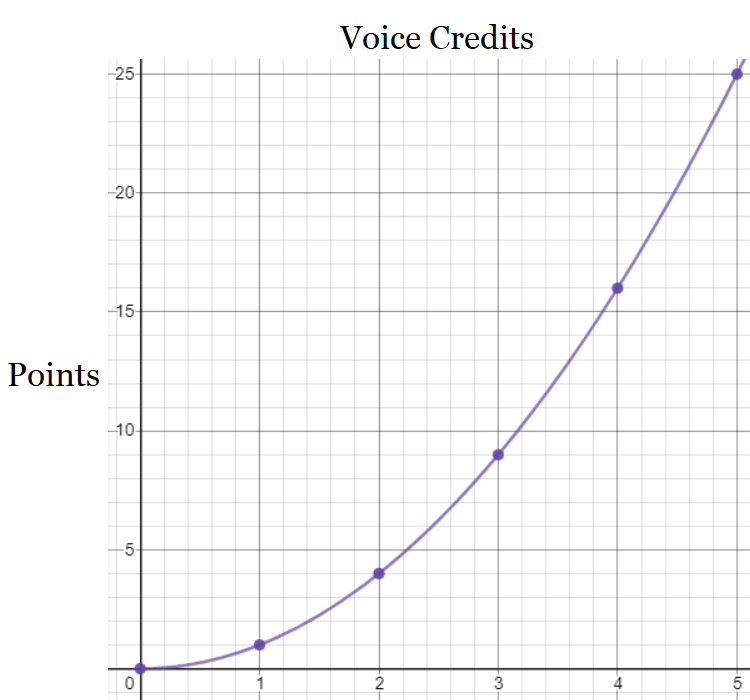

Now that we’ve formalized the types of OPOV more, we can move on to the other portion of this post’s topic: quadratic voting. Under quadratic voting, voters “buy” multiple points in favor of a single option using “voice credits”, and the option with the most points in favor wins. The cost of buying points for a given option is the square of the number of points being bought. This means that 1 point would cost 1 credit, 2 points would cost 4 credits, 3 points would cost 9 credits, and so on. Thus, the cost function ends up being quadratic.

In the previous OPOV post, I said that quadratic voting failed every type of OPOV. This is true for the version I just described, but it turns out that there are variations of quadratic voting that can pass different types of OPOV. This makes quadratic voting a useful tool for explaining how voting systems can be altered to pass or fail the various types of OPOV. In particular, I want to consider the scenario of quadratic voting being used in U.S. presidential elections.

Let’s start off by considering the case where all states switch to using quadratic voting, but still operate within the Electoral College system. We’ll assume that the voice credits persist over multiple elections, possibly (but not necessarily) because they are real currency. This means that different voters will have different amounts of voice credits in each election, and so some voters will be able to cast votes that others won’t. For example, a voter with 10 voice credits could give Candidate A 3 points and Candidate B 1 point since 32 + 12 = 9 + 1 = 10. In contrast, a voter with only 9 voice credits would be unable to cast this vote. Thus, this system fails the IIO criterion.

What happens when we modify the system to distribute a fixed number of voice credits to each voter in each election, without the ability to save them for future elections? Well, we’ve eliminated the issue of different voters being able to cast different votes, so the IIO criterion is now passed.2 However, because the Electoral College is still in place, it remains possible to change the outcome of many elections by changing which voters cast which votes in each election. Thus, the anonymity criterion is still failed.

Modifying this system to pass the anonymity criterion is straightforward; all we need to do is replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote. Now every voter is treated the same regardless of what state they vote in, so there is no way to change the outcome of the election by swapping votes around. However, it’s not always possible for one voter to perfectly cancel out the vote of another voter. For example, if each voter is given 100 voice credits per election and there are three candidates A, B, and C, then one voter can cast a vote that gives 10 points to A. Perfectly cancelling this vote out would require giving 10 points to B and 10 points to C, but doing that would cost 200 voice credits, so any voter with only 100 voice credits couldn’t cast a cancelling vote. Thus, the cancellation criterion is still failed.

At this point it might feel like we’ve modified quadratic voting to pass all the types of OPOV it possibly can. However, there is a way to modify it further so that it passes the cancellation criterion; instead of restricting voters to buying points in favor of an option, we also let them buy points in opposition to an option. This means that in the example above, the vote that gives 10 points in favor of A can now be cancelled by a vote that gives 10 points in opposition to A. In fact, it will always possible to construct a valid vote that cancels out another valid vote, as we can simply reverse whether the points purchased are in favor of or in opposition to each option. Thus, this version of quadratic voting passes the cancellation criterion.

I’m hoping this demonstration of modifying a voting system to pass each type of OPOV in sequence helps build intuition for how the types relate to one another and to the voting systems that pass and fail them. If some of the vaguer types seemed arbitrary, I also hope that my efforts to provide more formal criteria helped clarify things.

-

In both this post and the previous post on OPOV, I kind of conflate voting methods with electoral systems under the term “voting systems”. If this doesn’t bother you, you can just ignore it. If this does bother you, you can think about this matter purely in terms of electoral systems by applying a simple default electoral system as a “wrapper” around any voting methods that are mentioned. ↩

-

This assumes that for each state, all candidates either make it onto the ballot or can be written in. If this doesn’t happen, then IIO is still violated. ↩