The concept of one person, one vote is often brought up in discussions of voting methods and electoral systems. In the United States, it’s commonly associated with a Supreme Court decision that required states to use districts with approximately equal populations. However, the general idea that everyone’s vote should be equal has been brought up as a way to challenge alternative voting methods like approval voting and instant-runoff voting (abbreviated IRV, and also called ranked-choice voting), despite the fact that votes cast under these methods are not any less equal than the single-choice plurality method used in most U.S. elections. To make this even more complicated, this concept has also been used to argue in favor of replacing plurality voting with alternative methods. The Equal Vote Coalition’s equality criterion is a good example of this.

Having all these overlapping concepts associated with one phrase is likely to lead to a lot of confusion. For instance, Equal Vote appears to equivocate between two different meanings in their page comparing STAR and IRV. The section on equality begins with the following sentence:

The U.S. Supreme Court has found unequivocally that ‘One Person, One Vote’ requires that “each vote be given as much weight as any other vote.”

However, the page goes on to claim that IRV fails one person, one vote, which is not true under the Supreme Court’s definition. Instead, Equal Vote has switched to applying their own equality criterion. Without proper clarification, this is very misleading to readers.

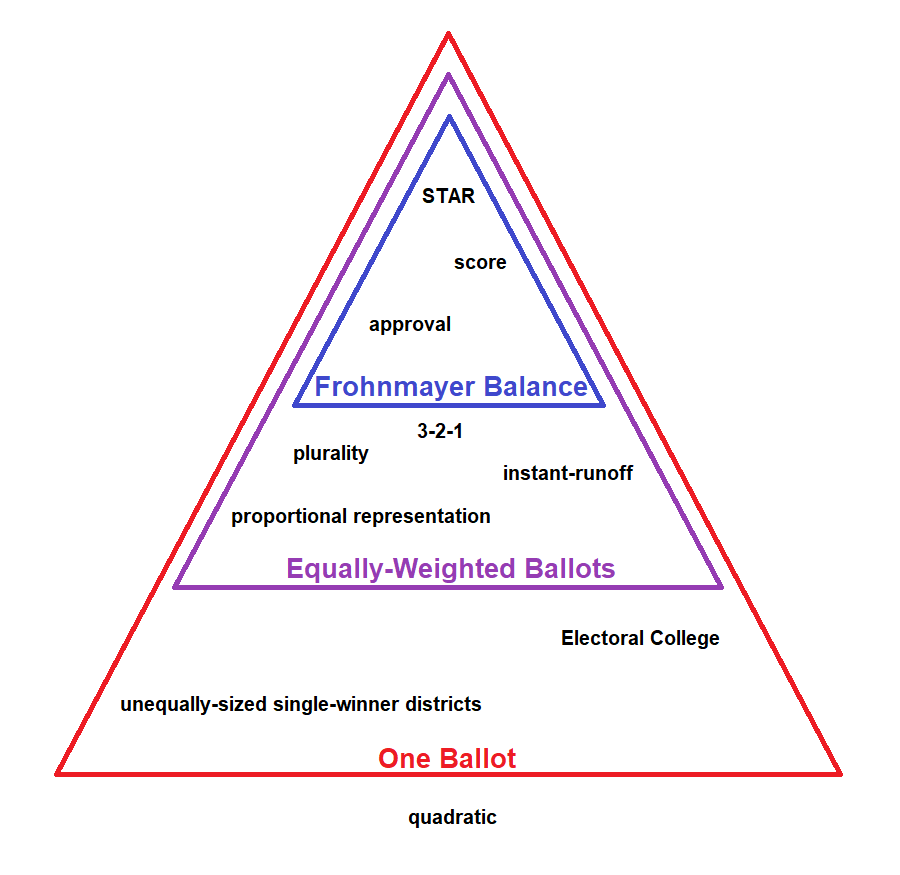

To help counter the confusion that can arise in this and similar situations, I’d like to construct a hierarchy of the various interpretations of one person, one vote. This hierarchy will have 3 levels, with each successive level being more restrictive than the last. Thus, passing the 2nd level means the 1st level is also passed, and meeting the 3rd level ensures that both other levels are satisfied.

The 1st level is the most literal interpretation of one person, one vote. It simply requires that every participant gets exactly one ballot. This is the version that some attempt to employ against methods like approval and IRV; their mistake is that they conceive of a vote as being a mark on a ballot rather than the ballot itself. When the latter conception of a vote is used, it becomes clear that pretty much any serious voting system passes this level of one person, one vote. However, an interesting exception to this is quadratic voting, which allows voters to “buy” multiple votes on a single issue using “voice credits”.1

The 2nd level of one person, one vote requires that every voter’s ballot be weighted equally. This is the interpretation used by the U.S. Supreme Court to eliminate unequally-sized districts at the state level, including a pair of districts where 41 times as many voters lived in one district as did in the other. Pretty much all voting systems satisfy this requirement, assuming they use districts of roughly equal size. Alternatively, the number of representatives for a district can be kept proportional to the number of voters in that district. Note that the Electoral College fails to do this, so it does not satisfy this level of one person, one vote.2

The 3rd and strictest level of one person, one vote is the previously mentioned equality criterion, also referred to as Frohnmayer balance. The Equal Vote Coalition describes this criterion as follows:

A voting method passes the Equality Criterion if every possible vote expression has a counter-balancing vote expression and if the counting system produces the same election outcome when any pairing of a vote expression and its counter-balancing vote expression are added to the tally.

In other words, when one person casts a vote, it must always be possible for another person to cast a vote that will perfectly cancel it out, regardless of how all other votes are cast. This is actually far more restrictive than the previous levels of one person, one vote. For instance, single-choice plurality voting fails this criterion, as does the popular reform option instant-runoff voting. It’s also impossible for any multi-winner voting method that achieves proportional representation to pass this criterion.3

Some of the few voting methods that do meet this criterion are approval voting, score voting, and STAR voting. To cancel out a vote when using approval voting, you simply approve all the candidates that weren’t approved on the other ballot. This results in each candidate receiving exactly one approval from the two ballots, keeping the differences between their totals the same. Under score and STAR, you have to give the candidates the ratings opposite of those on the other ballot. For example, using a scale from 0-5, a rating of 5 would be canceled with a rating of 0, a rating of 4 would be canceled with a rating of 1, etc. This ensures that the two ballots give each candidate exactly 5 points total. In the case of STAR, it also preserves pairwise results, so the winner of the automatic runoff will remain the same as well.

To summarize, the 1st level of one person, one vote requires that each voter have exactly one ballot. The 2nd level requires that each ballot have the same weight. The 3rd level requires that each possible ballot can be perfectly cancelled out by another possible ballot. To illustrate this relationship, I’ve created a helpful combination Euler/pyramid diagram:

-

It’s called “quadratic voting” because the number of credits needed to buy votes for a given issue is the square of the number of votes being bought (so 1 vote costs 1 credit, 2 votes cost 4 credits, 3 votes cost 9 credits, and so on). ↩

-

The U.S. Supreme Court’s interpretation of one person, one vote only applies to the states, so there’s no constitutional issue here. In fact, the Electoral College system doesn’t even require states to hold elections to decide how to choose their electors. ↩

-

There is a proposal for a similarly strict version of one person, one vote that can be passed by proportional methods called Vote Unitarity. ↩